Last Updated on November 17, 2017

“We learned how to face an unlearning challenge and offer suggestions on how to unlearn an existing way of thinking that may be impeding our problem solving process. Come unlearn with us!”

Generalizations are natural and useful for the human brain because they operate as a heuristic or a cognitive mechanism to quickly gather, process, and synthesize information.

As social animals, we seek to gather information about those around us. However, there is too much information to process all of it in its entirety. Therefore, we have these heuristics (such as generalizations and stereotypes) to make the process more efficient. In applying a stereotype, one is able to quickly “know” something about an individual.

For example, if the only thing you know about Helen is that she belongs to a band, you are able to guess that she likes music. People use stereotypes as shortcuts to make sense of their social contexts, making the task of understanding one’s world less cognitively demanding.

We generalize about people so that we know how to interact with them. If we see someone in a postal uniform, we assume they work for the post office. If we see someone who looks over 80 years old, we assume they are not in the workforce anymore.

But when did stereotyping become harmful for our society? And what can we do to change this?

When do generalizations move into stereotypes?

Stereotypes are over-generalizations, often involving the belief that a person has certain characteristics based on unfounded assumptions (the key word here being unfounded).

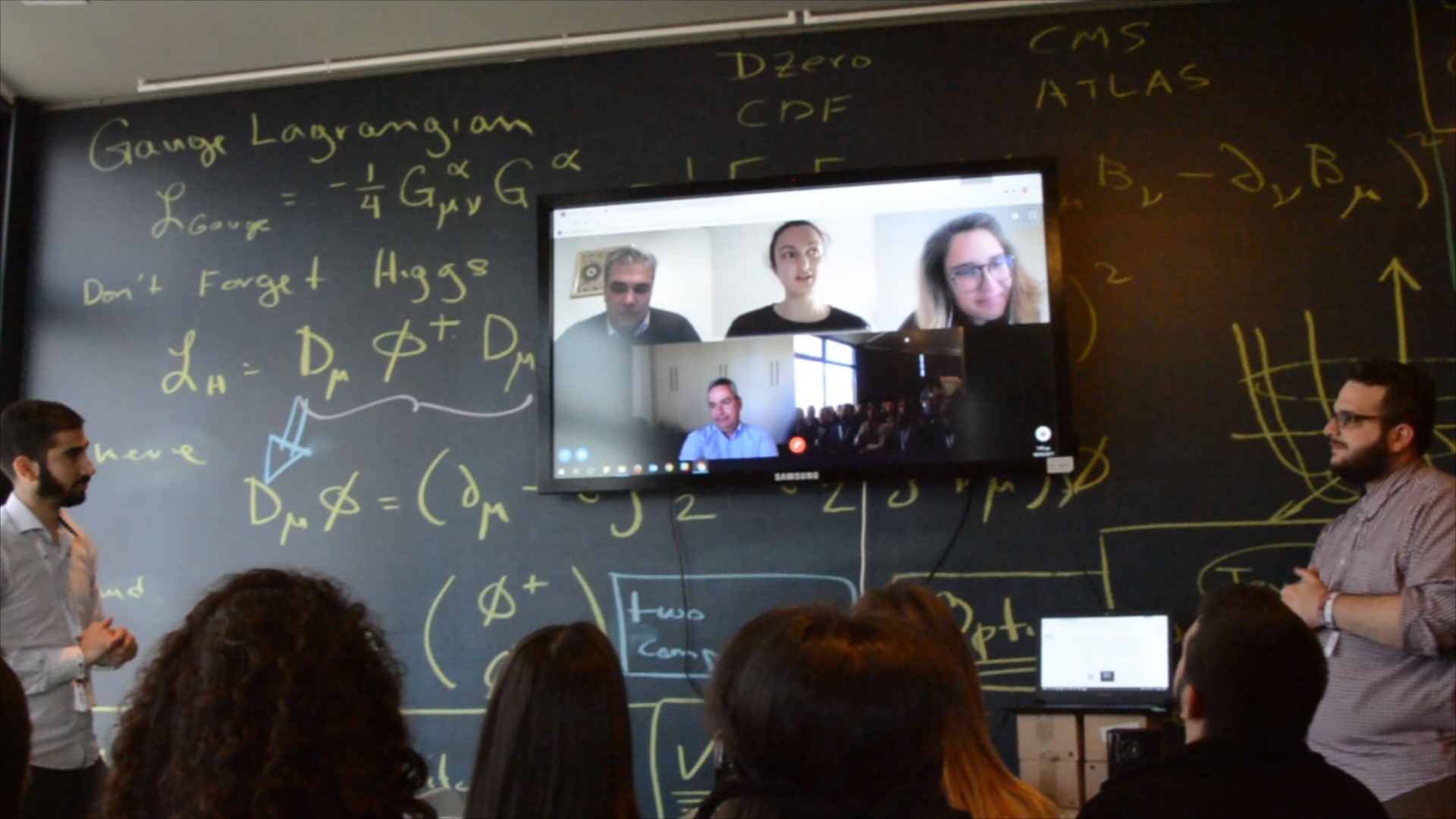

Let’s take an example. A few days ago during TEDxAUEB , 20 students participated in a guessing game. They were asked to judge four extraordinary individuals —a Strategy Consultant from The World Bank, a Design Coordinator from LAMDA Development, a research scientist from NASA ,and a Business Analyst from McKinsey & Company — based on first impressions.

The participants were asked to guess, and match each mentor to a job title, based on the mentors’ looks & answers. Here’s what happened during the three rounds of the game.

The participants were asked to guess, and match each mentor to a job title, based on the mentors’ looks & answers. Here’s what happened during the three rounds of the game.

Round 1: First Impressions

In the first round, the mentors were asked a series of questions:“What is your most important value, that constantly guides you through life?” and “How do you define success?”

Research has revealed that the first visual impression is one of the top factors into creating stereotypes. To prevent the automatic generalizations that may have been made based on first visual impressions, participants were blindfolded. After only hearing (but not seeing) the mentors as they shared their answers, the students submitted their first round of guesses.

Round 2: First (Visual) Impressions

In the second round, it was time for the blindfolds to come off. The participants could now see the mentors, who remained silent.

Now, what happens to our brain when we look at someone for the first time? According to the “thin-slicing” theory, it takes us about 15 seconds to observe someone and decide if we like him or not, while also making assumptions about their lifestyle and profession. Beyond this, it actually takes us less than a second to take a mental snapshot of someone and judge their competence, confidence, and likeability.

So, how did the “thin-slicing” theory apply here? After seeing the mentors, 92% of participants changed their answer.

The woman, the Strategy Consultant from The World Bank, was now perceived as a free-spirit architect. Whereas the architect himself was perceived as working at The World Bank.

Round 3: Final Instincts

To tie it all together and paint the full picture, the participants could now see and hear the mentors. After this, 14% of participants changed their answers.

When the participants were asked why they chose their guesses, they responded with heuristic-based answers such as: “I trusted my instinct,” “the architect talked about power so he would probably work at a multinational company,” and “the guy from NASA was too communicative to work as a scientist.”

Key Takeaways

At the end of the day, each of us has a biased world view because we can only see through the lens of our own perspective. We can only see what comes before us, we can only hear what is around us, and we can only read what stands in front of us. No one has the definitive version of reality, including the author of this concept.

Our identities and environments (race, class, gender, religion, sexual orientation, culture, etc.) inform our worldview. In turn, our worldview impacts how we view, respond, and react to every experience. Different perspectives create different worlds. But we are all living in the same world, aren’t we?

As humans, it is our responsibility to learn what stereotypes and biases are, how to recognize our own biases and move beyond them to a more balanced ability of evaluating and understanding people, to a more balanced mind.

After all, it’s all about perspective.

For even more perspective, watch the video recap of the exercise from TEDxAUEB:

Begin the unlearning process with 100mentors

100mentors is the platform and network empowering students to connect with mentors on-demand to guide them in their most important academic and career decisions. With 100mentors, schools enable students to open up their circles of influence to include mentors from 300+ universities and 500+ companies across the world. Broaden your horizons to begin the unlearning process. Ready to get started?